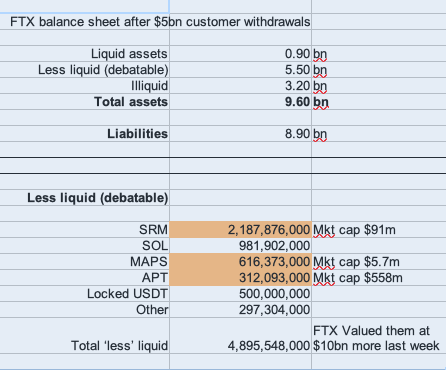

Over the weekend, the Financial Times published a balance sheet supposedly for FTX International and drawn up by FTX former CEO Sam Bankman-Fried. It’s clear from the document that when clients bought tokens that they ‘held’ at the exchange, FTX only kept a small proportion of assets that matched those tokens. The valuations given to some of the tokens on the balance sheet are fiction.

It highlights that there is still a lot more work to do after U.S. accounting body FASB’s decision that token valuations need to be marked to market. The two biggest fantasies are how FTX treated its own token and the value of other tokens that are not yet circulating.

As of two weeks ago, according to SBF, these assets were on the balance sheet at a value of $9 billion. Even on this recent balance sheet, they show up as $3.4 billion when they should be close to zero.

There’s been a lot of talk about FTX leveraging its own FTT token and using it as collateral. Much of this is based on the obvious risk that the token value could go to zero. So far it has dropped from $22 to $1.60.

But there’s more to it than that.

Why the FTT token is not an FTX asset

FTT is accounted for as an asset. Really it should not be on the balance sheet at all. And some might even consider it a liability.

As a utility token, one of the benefits provided to FTT token holders is discounts on FTX trading fees. There was also the usual ‘tokenomics’ with FTX ‘buying’ and burning FTT equal to one third of all exchange fees, in theory, to restrict token supply and pump the market price. Additionally, FTX allowed exchange users to use FTT as collateral for trading.

The weird thing here is that FTX accounts for FTT as an asset because it’s a tradable token and hence has ‘value’. It’s not alone in the crypto community. But outside of the crypto world, the token would not be on the balance sheet. If it were, it might be considered a liability because FTX owes its customers future discounts on trading fees.

Say Starbucks sold a million $10 gift cards to its customers. Starbucks gets $10 million in cash, and the other side is a liability of $10 million to the customers. When the gift cards are redeemed, the liability is reduced and the coffee bought with the card is recognized as a sale. So gift cards that are sold are more like a client prepayment.

But nowadays, many token issuers skip the ICO or IDO, so they don’t sell the tokens in order to avoid falling foul of securities laws. Instead, they give away the tokens. In which case, perhaps a token is closer to a coupon that provides you a discount on goods or services. Where do real world companies put coupons on the balance sheet? They don’t. When a coupon is redeemed, the sale is recognized in the usual way and the discount is an expense.

If FTT hadn’t been a crypto token and instead a coupon, it would not be on the balance sheet at all. Alternatively, if it’s a security, a company never holds its own shares as an asset.

This is hardly the first time token issues have been raised. Animoca Brands, the most prolific investor in NFT infrastructure and gaming, had its shares suspended in 2019 from the Australian stock exchange ASX over token accounting issues. In June this year, it was fined by the securities regulator ASIC for failing to publish accounts as a public company. Despite firing Grant Thornton as its auditor, it has since attracted investment from Japan’s largest bank, MUFG and Singapore government-owned investment firm Temasek.

In fairness to Animoca, in its latest accounts, it did not put its own reserve tokens on the balance sheet. That’s despite the company estimating the value in billions. Even if the tokens are not on the balance sheet, investors treat them as if they are.

Locked or yet to be issued tokens

The second FTX balance sheet fantasy relates to locked or yet-to-be-issued tokens. Many token issuers have massive issuances, but they eek out the token distribution over years. On FTX’s balance sheet, the SERUM and MAPS tokens show up as assets at many times the valuation of the current entire token market capitalization. The MAPS token appears on the balance sheet as worth $616 million, more than a hundred times the token’s current market cap of $5.7 million.

Extrapolating current tokens’ (tiny) value to a supply more than a hundred times greater makes no sense. If a listed company had 100 thousand shares in issuance and suddenly issued another ten million shares, would the stock price stay the same? Don’t be ridiculous.