With the shuttering of Silvergate, Silicon Valley and Signature banks in less than a week, there’s plenty of analysis about what went wrong. The triggers boil down to five factors: rapid deposit drawdowns, weak risk management, cryptocurrency, interest rates and an accounting issue that had a major impact on Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) situation. SVB was arguably bust months ago.

Silvergate succumbed to regulators

Silvergate went first, but it was an orderly shutdown. Through conservative risk management, it endured a run on the bank in the fourth quarter. But it continued to suffer losses on its sale of government bonds. Last week it decided to close voluntarily without the need for FDIC insurance. It stated the shutdown was “in light of recent industry and regulatory developments.”

Silicon Valley Bank was kinda bust last year

SVB’s demise was largely due to timing related to Silvergate’s shuttering and pattern recognition by SVB clients causing its run. So the impact of cryptocurrency was indirect through Silvergate worries. However, by some measures, SVB was insolvent by the end of Q3 2022.

Much of SVB’s issues related to risk management, holding longer-dated Treasuries. It didn’t help that it lacked a Chief Risk Officer from April 2022 until this year. SVB had one of the lowest bank loan-to-deposit ratios, meaning it held a higher proportion of Treasuries than most banks. When interest rates started to rise, it incurred significant losses on those large quantities of Treasuries.

However, an accounting issue meant that SVB was effectively bust by the end of September 2022, even if its accounts didn’t say as much explicitly.

If companies plan to hold fixed income securities until maturity (‘held to market or HTM’), they can amortize the debt rather than mark the value to market prices. The logic is they will get their money back in full at maturity, so market prices don’t matter. By the end of September 2022, SVB’s unrealized losses on these HTM securities were $15.9 billion compared to total equity of $15.8 billion. If it needed to sell any of those securities, its equity was wiped out. Because of the accounting treatment of fixed income securities, the losses were not reflected in the balance sheet, though they were in the notes.

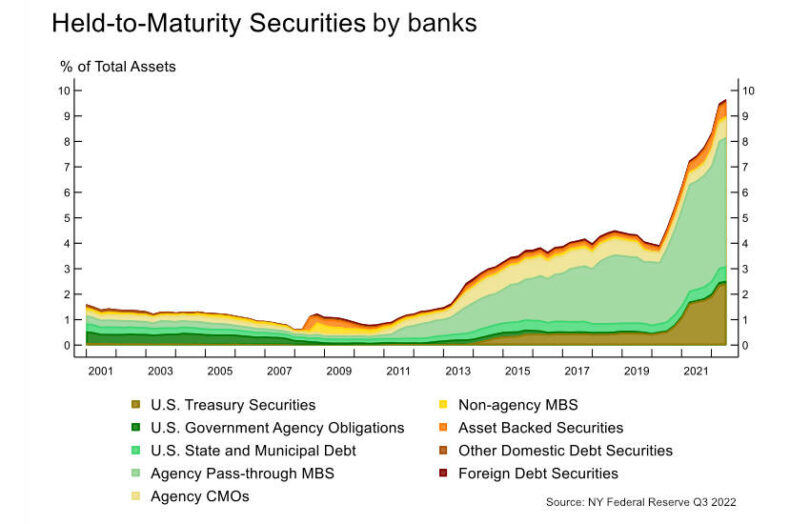

The proportion of assets held to maturity by banks has risen significantly, which is part of the reason why regulators stepped in to shore up liquidity. Even though the securities are perfectly saleable, if the banks sell them they have to recognize far larger accounting losses.

As tech companies withdrew funds because they were less profitable, SVB couldn’t sell any held-to-maturity assets. If it did, it would be clearly insolvent.

Last week SVB announced it had incurred a $1.8 billion loss on selling securities that were accounted for as ‘available for sale AFS’, where the price is marked to market. This left a hole. SVB’s problem was its need to raise more capital which, combined with the $1.8bn loss and Silvergate’s demise, spooked investors. And rightly so.

What happened with Signature?

Signature Bank was a lot more diversified than crypto bank Sivergate with a far smaller proportion of exposure to the crypto sector. However, because of Signature’s label as a crypto bank, since Silvergate disclosed losses in January, Signature was regularly reassuring the markets.

The local regulator shut down SVB because it couldn’t meet cash demands. While Signature had a similar experience, fewer details were provided. According to Bloomberg, one of Signature’s directors, Barney Frank of Dodd Frank legislative fame, reckoned that Signature wasn’t insolvent.

“I understand the deposit outflow,” he told Bloomberg. “But I think it was a classic case of being illiquid but not insolvent, and being illiquid for exogenous reasons that would’ve been corrected.”

But the Federal Reserve and FDIC concluded there was systemic risk.

With the close of both Silvergate and Signature within less than a week, the loss of the major cryptocurrency on and off ramps means the community is crying foul, saying regulators are trying to either isolate crypto or destroy it.

Two major digital asset players, Coinbase and Paxos, each had around a quarter of a billion deposited at Signature.

Signature’s stock had dropped a third since the collapse of FTX compared to a flat Dow Jones US Banks Index. And it lost another third last week. The likelihood of an extended run today was high, given the Silvergate – SVB experience. So regulators decided not to wait and nip contagion in the bud.

Meanwhile, the crypto community might be leaning into isolation. The largest exchange Binance has a relief fund, the Industry Recovery Initiative, which has a significant holding in its own BUSD stablecoin (which has to be shut down within 11 months). It’s switching $1 billion into crypto, including some into its own coin.

Hat tip to Marc Rubenstein