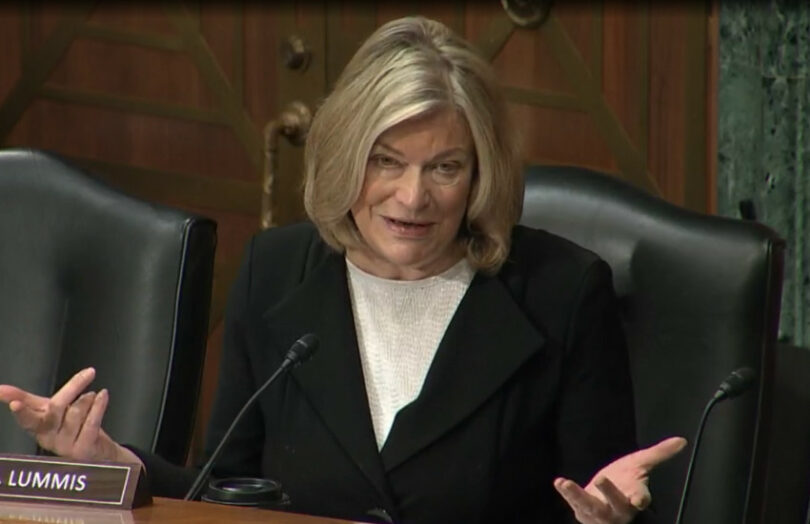

Yesterday U.S. Senators Cynthia Lummis (Republican) and Kirsten Gillibrand (Democrat) released a bipartisan Bill, the Lummis-Gillibrand Payment Stablecoin Act. It addresses several of the contentious issues in the separate House Stablecoin Bill, which reportedly have been resolved. The new Bill provides a balance between Federal Reserve and State regulator involvement. A stablecoin issuer can only be owned by a predominantly financial business, ruling out the likes of Meta, Google, Amazon and X.

The Bill proposes to ban algorithmic stablecoins.

Various iterations of the older House Stablecoin Bill covered issues not directly related to stablecoins, such as CBDC and diversity. The Senate Bill substantially avoids this, with one exception.

Article continues …

Want the full story? Pro subscribers get complete articles, exclusive industry analysis, and early access to legislative updates that keep you ahead of the competition. Join the professionals who are choosing deeper insights over surface level news.