Last week the World Economic Forum published a paper exploring the choice between public and private blockchains for enterprises in the supply chain sector. It emphasized that it’s not a one size fits all decision and depends on the objectives of the blockchain.

A private blockchain is often referred to as a consortium blockchain where a group of companies agree to collaborate in a private permissioned blockchain. Sometimes a technology provider will operate the blockchain, and the enterprises are customers.

On the other hand, a public blockchain like Ethereum does not limit access for participants. And anyone can be a node or server operator. Additionally, all transactions are available to the public.

It’s possible to encrypt some aspects of transactions on both public and private blockchains. A common alternative is instead of storing actual transaction details, to write a “hash” or digital fingerprint of a transaction to the blockchain. That way, the contents are kept separately and privately, and it’s not possible to derive the data from the hash. Hence if the transaction is manipulated, the hash will no longer match the underlying data.

The WEF document points to most enterprises adopting private blockchains in the near term. But states that as experience evolves that “there is hope it will open the way for increasing use of public chains in applications, where appropriate.” Over time public blockchains will also evolve to meet more enterprise application criteria.

Those criteria include clear contractual agreements; the ability to comply with know your customer regulations; interoperability with current systems; security and privacy requirements; and scalability.

Public v Private blockchain considerations

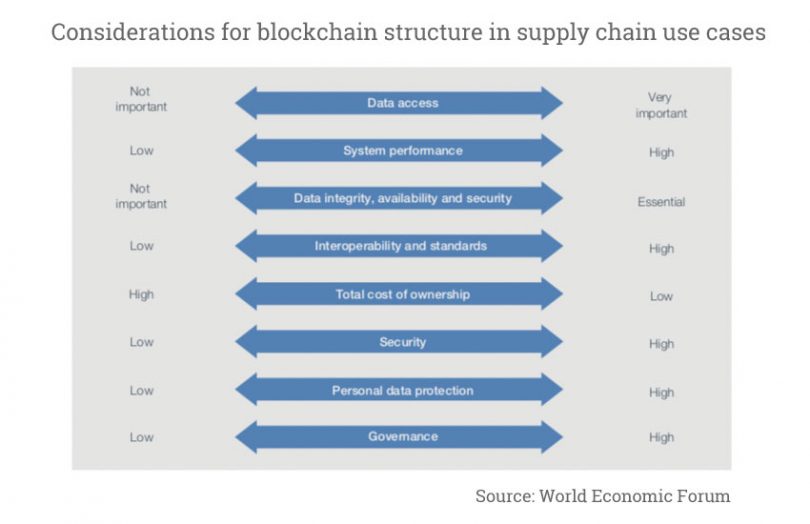

Most of the WEF document explores the considerations shown in the graphic. For data access, generally public blockchains provide far greater access to data and less control over who can see data. However, encryption and hashing can help. In situations such as energy prosumers accessing an energy marketplace, a public blockchain makes sense.

In private blockchain deployments access is based on permissions. Additionally, in some cases, the data is segregated, so participants store only data for transactions in which they participate.

When it comes to system performance, private blockchains tend to win because there are fewer participants to come to a consensus.

That comes with a trade-off on data integrity and security. While it’s hard to tamper with a private blockchain because there are multiple copies of the data, collusion is conceivable. That compares to a large public blockchain where it’s extremely hard or expensive to tamper with data.

The WEF argues that public blockchains are more interoperable today than private ones. Technically that is true. At the same time, it notes that private blockchains tend to develop shared standards.

We’d argue that because these shared standards are more industry-focused, they can sometimes trump the generic interoperability offered by public blockchains. In fact, enterprise blockchain often drives the development of shared standards. In turn, these standards can be more useful than the blockchain implementation itself.

How much does it cost?

In terms of the total cost of ownership, most public blockchains are likely to win easily in the startup phase. That’s because public blockchains are designed to have very low barriers to entry and charge “gas” for transaction fees.

In contrast, a private network and its nodes have to be set up and maintained, which is not an insubstantial cost. That said, the vast majority of funds are spent on application development (similar cost for public and private) and setting up a governance structure which is specific to enterprise blockchains.

When it comes to personal data protection, the WEF leans towards private blockchains. It says: “a robust data protection impact assessment is a must for GDPR compliance with public chains.”

And for governance, enterprise blockchains provide far greater control. But the WEF emphasizes the need to consider diverse interests within the ecosystems, particularly different types of participants such as shippers versus intermediaries.

Alternatives: public permissioned

There are several public permissioned blockchains now in existence. Generally, the data is public, but the node operators are permissioned. Two examples mentioned were the Sovrin identity blockchain and Wave for bills of lading.

The paper concludes that it’s hard to predict the future of blockchain in 10 to 15 years.

“Given this uncertainty, decision‐makers would be best advised not to get distracted by the public‐versus‐private debate and to stay focused on the context of their selected use case and distinct requirements.”

The paper is the third in a WEF series addressing supply chain blockchains. The first focused on inclusive deployment and the second on verifying digital identities. Three weeks ago the WEF also released a framework developed with Accenture to evaluate blockchain benefits.