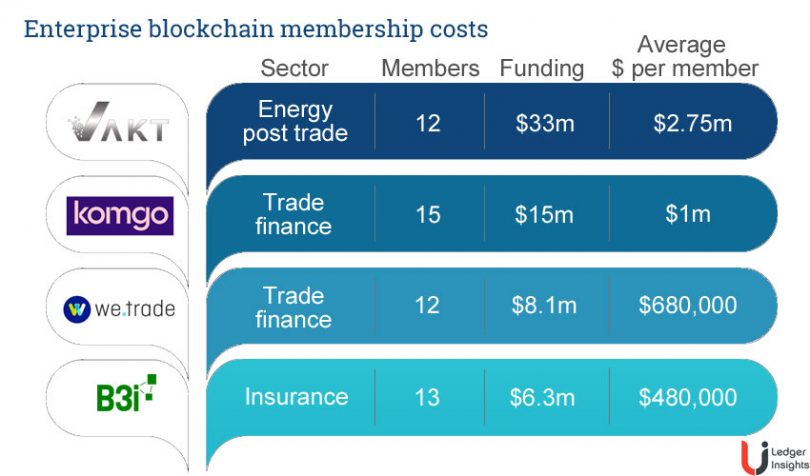

Enterprise blockchains are consortia by their nature, so the cost is spread over member investors. But spreading a large investment can still involve a significant outlay. The question is how much does it cost to join an enterprise blockchain consortium? And the obvious answer is “it depends”. We’ve uncovered the specifics of four large initiatives. The current funding for those projects ranges from $6.3m to $33m giving an average investment per member of $1.2 million.

In three out of the four, the company average investment is roughly representative of the amount paid by all shareholders, except for VAKT where the average represents a broad range from $1m to $5m. The number of shareholders for the four companies varies from 12 to 15.

With just four projects, it’s hard to claim that they’re representative of all enterprise blockchains, particularly because the two substantially better-funded projects, VAKT and komgo, have numerous energy sector investors. On the flipside, B3i the insurance initiative is likely to close its second funding round soon, and hence its figures are understated.

In sectors where technology providers are creating blockchain solutions, there’s an alternative to investing in a consortium-like company. Adopting a third-party solution can involve less initial outlay but also cede ownership of the IP to the solution provider. Here the focus is on ownership.

In most conversations with Ledger Insights, companies are tight-lipped about investment figures. But the anecdotal evidence indicates a price tag between $500,000 to $1 million for the first 1 – 2 years in start-up funding by member investors.

Some might argue that the cost is high, others might think it’s cheap. But it’s not the cost that matters. What remains to be seen is the return on investment.

Here’s a look below at how sponsorship works:

Sponsors and payment in kind

It’s not unusual to have one or more sponsors who initiate the project and bear the costs at the very early stages. Sometimes these sponsors are compensated with a higher equity stake, but not always. In other cases, the payback is primarily getting the project off the ground.

For example, in insurance, The Institutes RiskBlock Alliance received seed funding from The Institutes which provides professional development for insurance in the U.S. This financing meant that, initially, members paid what Nationwide referred to as “fairly small” contributions. RiskBlock is a non-profit, so there’s no equity to invest in, just intellectual property.

For komgo in trade finance, the project was started by ING, Société Générale and ABN Amro, which developed software and ran prototypes for more than a year before incorporation with 15 shareholders. Each shareholder holds one-fifteenth of the company’s shares. However, CEO Souleïma Baddi confirmed to Ledger Insights that “the other shareholders paid a little bit more to get the same amount of shares than the founding partners to recognize the IP that has been developed.”

So the full project cost may not be reflected in the figures because some of the expenditure was incurred before incorporation. What’s surprising is that in some cases the project initiators are not demanding a greater stake for their early commitment.

In the case of the we.trade trade finance platform, KBC bank created a prototype in 2016 and a consortium of seven banks formed in early 2017. The members increased to nine when Santander and Nordea joined later but before the company formation. The initiative incorporated at the end of Q1 2018 and all shareholders were treated the same and held equal shares until late 2018. That said, the two late joiners did not get a free ride. The pre-incorporation consortia costs were split into a per node (effectively per bank) cost. And the two new participants paid an equivalent amount for their nodes.

Trade finance

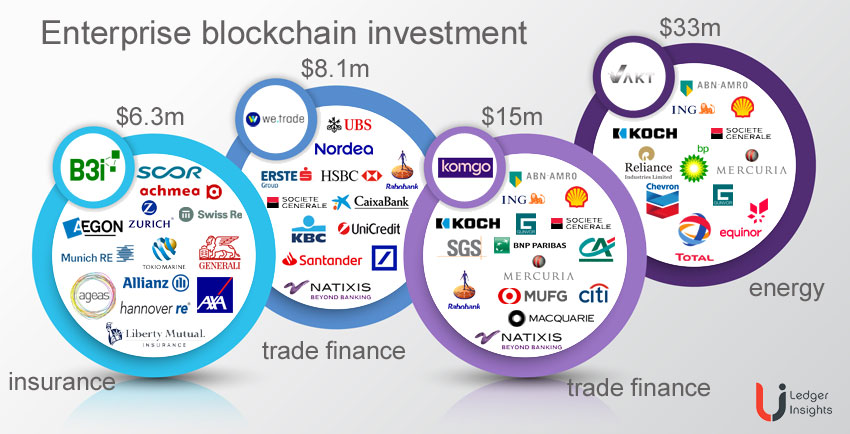

We.trade was the first consortium-style enterprise blockchain to launch. Shortly after it went live trade finance blockchain initiative Batavia disbanded and three of its five members – Erste Bank, Caixa and UBS – joined we.trade, investing €500,000 ($570,000) each and increasing the shareholder count to 12.

We.trade raised €3.65 million ($4.1m) at incorporation in Ireland in March 2018, and a further €3.5 million ($4m) in November giving a total of €7.15 million ($8.1m). The November round comprised €2 million as the second round of funding and €1.5 million from the new investors. The average shareholder investment since incorporation was €596,000 ($679,000). If all investors participated in the second funding round, then original investors would have paid €572,000 compared to €666,667 for the new investors for their one-twelfth stake.

However, the Irish Company Registry showed that UBS chose not to participate in the second funding of €2 million and thus holds a slightly smaller shareholding than the others. Hence, we asked COO Roberto Mancone about the difference and he said that “the banks could pitch for more of the shares offered or for less. Some banks decided to participate. UBS, in this case, decided not to, but we’re talking about a minor amount of difference in shares in terms of percentage [ownership].”

Meanwhile, komgo, the Geneva-based trade finance project focused on the commodities sector, has 15 founding shareholders composed of ten major banks, four energy companies and traders, and SGS the certification company. The total investor commitment was 15 million Swiss Francs ($15.15 million) for the first 18 months. The second round of funding is likely to include new investors who will spread the load.

VAKT for energy post-trade

VAKT, the London-based blockchain platform targeting post-trade for energy, has seven shareholders in common with komgo. The founding shareholders created a separate company for trade finance so that komgo can additionally target other commodities such as agribusiness and metals.

VAKT started in early 2018 with nine shareholders and an initial funding round of $8.9 million. A second funding round of $9.1 million followed in August after a move of jurisdiction to London. In December three new members—Chevron, Total and Reliance Industries—joined paying $15 million for their shares, bringing the total funding to $33.1 million and an average of $2.75 million per investor.

The first two rounds cost between $33 and $34 per share (adjusted for share split). But the December share issue cost four times more at a price of $137.86 per share. Most of the original shareholders hold just under 10% for which they paid roughly $2.17m. Except for Société Générale which invested $1 million for a 4.6% stake. And the new shareholders each paid $5 million for a 5.56% holding.

B3i for insurance

The Blockchain Insurance Industry Initiative (B3i) incorporated in Zurich in March 2018. Three insurers and two reinsurers started B3i in October 2016. It expanded to 15 founding members in 2017, and 13 of those members were involved in the incorporation. The founding share capital was 6.3 million Swiss Francs ($6.4m), of which 4.5 million Swiss Francs ($4.5m) related to intellectual property (IP) developed before incorporation.

CMO Ken Marke explained that the 15 original members were “compensated for their IP contribution in shares or cash depending on preference of the participating party”. The compensation is the same value for each. B3i Services AG is a private company but it is clear that with 13 shareholders registered, the two companies that did not continue as shareholders would receive another form of compensation at some point.

That gives an average shareholder commitment of 492,000 Swiss Francs ($497,000) to date. However, the company is currently in the advanced stages of a second funding round. Depending on how much any current or new shareholder invests, the equity is likely to be less equally spread going forward.

Update: Since the publication of this article B3i announced a Series A round which included multiple follow on investors and raised at least $28 million from 18 shareholders.

Comparing apples-to-apples

One might expect that not all members are created equal. However, several enterprise blockchains demonstrate a desire to give shareholders as equal treatment as possible. And in some cases, early seed investors are only receiving basic compensation and tend to have an equal shareholding. But going forward, as each shareholder commits varying amounts of cash, the even spread of equity will not be maintained. For VAKT, later entrants are already paying far more.

Furthermore, some enterprise blockchains such as we.trade claim to be “utilities”. Here the shareholder’s primary motivation is to leverage the technology internally within the shareholder’s organization, rather than for the blockchain company to become hugely profitable. As the shareholder base expands beyond core customers, the demands on these “utilities”, particularly concerning return on investment, may evolve.

At the end of the day, everyone is after a return on investment. And it stands to reason that those members who took greater risk will also reap greater rewards when these platforms take off, and the rewards start coming in.