In case you missed it, on Friday the Buybit cryptocurrency exchange suffered a hack, losing 401,000 in Ether cryptocurrency, worth around $1.1 billion plus others worth over $300 million. The North Korean Lazarus Group is thought to be responsible. Looking a few years into the future, if someone sold a large amount of digital securities, wouldn’t that problematic with the hacking risks?

The answer is not really.

There’s a big difference between a decentralized cryptocurrency like Ethereum, and digital securities with an identifiable issuer. Most tokenized or digital securities that are issued in a compliant fashion retain some kind of control. That means if there’s a big mistake, a fraud or a theft, it’s possible for the issuer to step in to right the wrong. They can block the asset or potentially transfer the tokens to another person.

Depending on the token design, that’s just as possible on a permissionless blockchain as it is on a private one. The ‘permissionless’ aspect applies to the blockchain itself, not necessarily the assets that sit on top of it.

So, fears of hacks are not really a definitive reason to resist permissionless blockchains for traditional securities. It doesn’t mean a hack wouldn’t be very inconvenient, and could potentially involve litigation given prices move. But in most cases it should not be a major disaster.

What about censorship resistance?

Enthusiasts of decentralization dislike the ability to freeze tokens because they prefer ‘censorship resistant’ assets. By contrast, the biggest stablecoins such as Tether and USDC are fully centralized and support freezing.

In the Bybit case, a small proportion of the theft was converted into Tether stablecoins, which Tether promptly froze.

Decentralization enthusiasts have created stablecoins which make it harder for this type of intervention. The DAI and its Sky successor was originally amongst this group and the M^0 protocol does not have freezing in its core functionality, although it allows others to optionally built this on top.

Supporters of decentralization, aren’t necessarily in favor of the Lazarus Group or thieves. Instead, most don’t want to see a repeat of what happened in Canada during COVID, when protesters had their bank accounts blocked.

Meanwhile, if you want to know how the hack happened, when Bybit was transferring funds to its cold wallet, the hacker managed to fake the user interface, so the funds went to the wrong wallet. More details are here. Without acknowledging fault, the Safe wallet provider has rolled out a new version of its software, removing the method that Bybit used to sign its transactions.

What will happen to the stolen ETH?

There was some chatter about potentially rolling back the Ethereum blockchain to a point before the hack, in order to return the funds. But that’s unrealistic. A rollback happened in 2016 in the early days of Ethereum after the DAO hack. It was hugely controversial then. Now it is likely impractical given all the transactions that have taken place subsequently.

Before the Lazarus Group was identified as the hacker, there were hopes that most of the funds might be returned.

The hackers are likely to use mixers to get fresh token addresses to cover their tracks.

However, there is a path to making it hard for the Lazarus Group to use the funds, even if it doesn’t help Bybit.

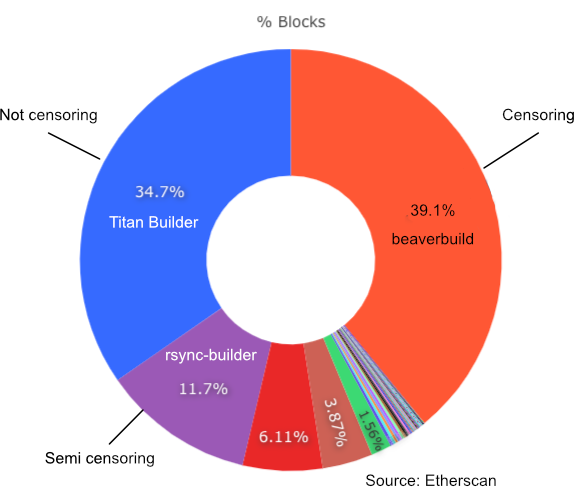

During the past 24 hours, 85% of blocks on the Ethereum blockchain came from just three block producers. At the settlement layer, if block producers refused to include transactions from these wallet addresses, then the hackers wouldn’t be able to use the tokens, not even via mixers.

Of those three large block producers, one does not censor transactions, one does, and one partially censors. However, to stop Lazarus, all blocks produced would have to censor their wallet addresses.

Earlier this month, the New York Federal Reserve published a post on this topic, exploring which producers include transactions from certain mixers. They concluded that even blockchains like Ethereum “are apparently not immune to the potential for certain transactions to be excluded due to external pressure.”