It’s been two years since the Deutsche Bundesbank unveiled tests for a trigger solution to settle DLT securities transactions with central bank money. This links the securities DLT to Europe’s TARGET2 real-time gross settlement system (RTGS) and is viewed as an alternative to a wholesale central bank digital currency (wholesale CBDC).

This month two Bundesbank payments executives outlined why the central bank considers a trigger solution as a wholesale CBDC, even though many expect a wholesale CBDC to be an on-ledger token. Benoît Cœuré, when he was leader of the BIS Innovation Hub, stated that blockchain tokens were the distinctive feature of wholesale CBDC.

In a SUERF policy note, Martin Diehl and Constantin Drott argue that the distinguishing aspect of a wholesale CBDC is its programmability rather than tokenization. The other key features are its restricted access and non cash central bank money, but these two apply equally to conventional wholesale central bank money.

The central bank wants to “keep money within established systems instead of prematurely putting cash on the ledger,” given the adoption of DLT is still relatively nascent.

They clarified their concerns about a tokenized wholesale CBDC and how they envisage a trigger payment solution should work.

How a trigger solution might work

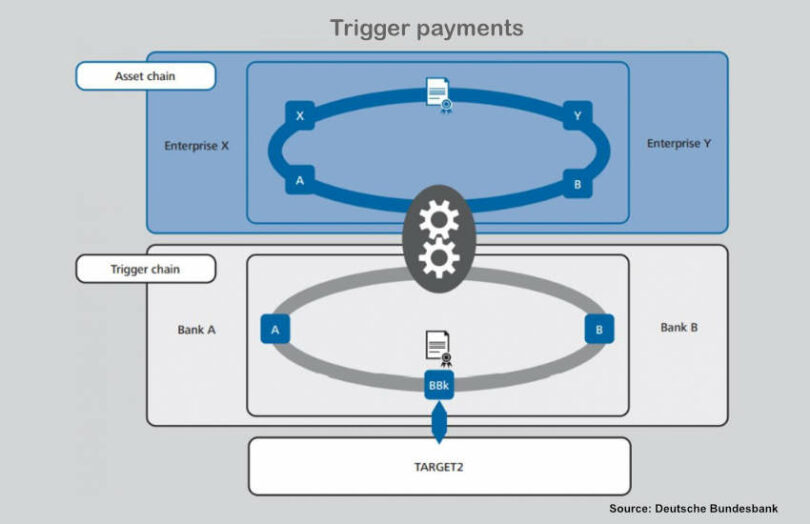

The Bundesbank outlined a three layer solution. There’s an asset chain in which enterprises can be involved and a trigger chain as a programmability layer where only commercial banks and central bank participate. In turn, the trigger chain links to the RTGS to trigger the payments.

It argues that it could support any asset chain and that the trigger chain can be used for numerous use cases. It simply needs a bank-signed payment instruction. Additionally, the trigger chain could connect to multiple payment systems, not just TARGET 2.

Objections to a tokenized wholesale CBDC

Fragmentation of liquidity is presented as a key objection to tokenized CBDC. However, the other objections, which may be perfectly valid from a central bank perspective, indicate that the real issue is a potential loss of central bank control.

Regarding fragmentation, the argument is that tokens on each ledger have to be pre-funded, resulting in pockets of money locked in different places. This is an objection we’ve seen elsewhere, including from the Bank of Italy.

Is it possible that this overlooks the programmable nature of a tokenized CBDC? For example, suppose a bank has a CBDC balance on one particular ledger. It might check to see whether there is any need for it, and if not, it could instantly transfer it to its central bank account or convert it into a token on another ledger. The counterargument is that RTGS systems do not operate 24/7, so conversion may only sometimes be available. But trading cash on one ledger for tokens on another DLT could function around the clock.

Turning to control issues, the central bank would need to oversee multiple ledgers where its currency is used and believes it may not have access to the same degree of data. Because central bank money would exist on multiple ledgers, it might hamper speed central bank intervention. And it’s concerned that the differentiation between central bank and commercial bank money might weaken.

The paper acknowledges that two critical benefits of DLT are programmability and the removal of the need for reconciliation through a shared ledger. The proposed trigger solution might address programmability, but without on-chain cash, reconciliation is still a requirement. This reduces the financial benefits of adopting DLT.

On the one hand, the central bank’s view that one should wait and see if DLT platforms take off appears valid at first. And providing some solution, even trigger-based, is better than nothing. On the other hand, some believe that cash on ledger is one of the critical pieces of the puzzle needed to progress DLT implementation.