Today the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) published a chapter from its annual report entitled “Central banks and payments in the digital era”. Part of the section covers central bank digital currencies (CBDC), which it considers an increasingly likely option. If there was one takeaway, it was that it sees the role of a central bank as the guardian of private sector competition for payments.

“CBDCs could offer a new, safe, trusted and widely accessible digital means of payment,” the paper states. “But the impact could go much further, as they could foster competition among private sector intermediaries, set high standards for safety, and act as a catalyst for continued innovation in payments, finance and commerce at large.”

It briefly addresses private sector attempts to address the demand for faster and cheaper payments. It references Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, Libra’s stablecoin, and big tech and fintech firms’ entrance into financial services.

“Some of these have failed to gain much traction; others are perceived as a threat to jurisdictions’ monetary sovereignty; while many have yet to address a host of regulatory and competition issues,” says the report.

That was the sole direct mention of Libra in the 28 page document. However, the specter of Facebook’s 2.6 billion userbase was evidenced in the mention of ‘competition’ no less than 46 times in the paper. While Libra may have morphed to address regulatory compliance requirements and maybe monetary sovereignty, it’s hard to see how it might appease regulators when it comes to competition concerns. Today’s announcement of a block by Brazil’s central bank on newly launched WhatsApp Pay is further evidence of this.

But it’s not just Facebook at which the competition message is aimed. The BIS highlighted the network effects of payment systems, which by their nature, result in dominance by a small number of players. Good examples not explicitly mentioned are Visa and Mastercard in the West and Alipay and WeChat Pay in China.

A metaphor repeated in the BIS document was that of a town market, where the provision of a public square provides the foundation for competitors to show off their wares. Likewise, a central bank provides the payment infrastructure so that payment service providers can compete and innovate. And a CBDC backbone could be one such platform.

Otherwise, it sees big tech and fintech representing a major threat to incumbent players. The BIS believes public intervention may be required to ensure interoperability, with open banking as an example.

To ensure open competition, it was emphasized that new technologies and players have to adhere to the same regulatory standards as everybody else.

When it comes to CBDC, the BIS acknowledges that usability is essential and best provided by the private sector. It also wants to address the risk of funds flowing out of commercial banks during a crisis, either by offering a lower interest rate or capping the retail holdings of CBDC. Data portability between providers and privacy need to be balanced with anti money laundering needs.

Ultimately the BIS envisions a two-tier system for CBDC with a central bank operated infrastructure. It positions CBDC as a complementary means of payment, to address specific use cases and market failures, and a catalyst for innovation.

The paper mentioned the need for infrastructure resiliency without mentioning that one of the stated aims of China’s digital yuan is to address resiliency concerns given the reliance on WeChat Pay and Alipay. If one of those payment systems went down, it could have a dire impact.

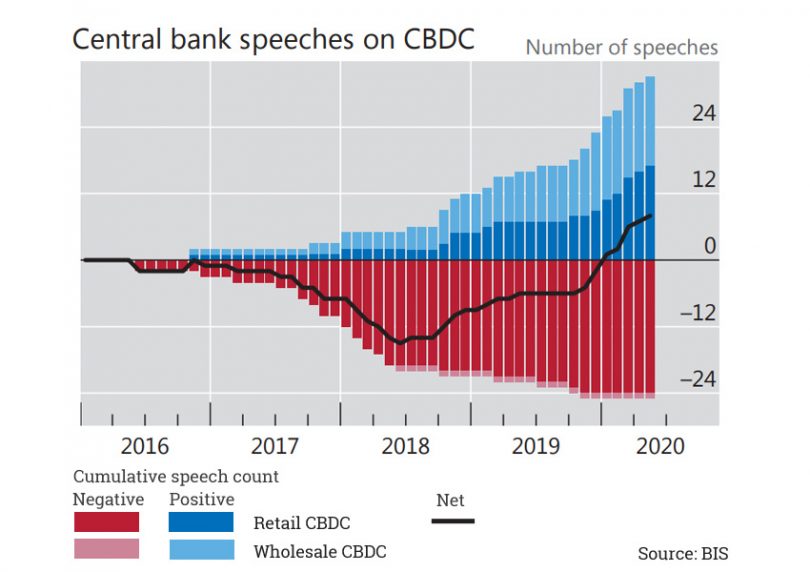

The BIS acknowledged that retail CBDC is being discussed more and has higher risks because a wholesale CBDC is not fundamentally different from the status quo. From a value perspective, the amount of work involved in a retail CBDC is disproportionate (our view, not theirs). Its CPMI statistics speak for themselves: Retail payments account for 90% of payment volumes, but only 1% of value.