There have been a few publications that explore privacy enhancing technologies (PETs) for payments and central bank digital currency. The latest paper on the topic from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) takes a different approach. It starts from first principles and explores the inherent tension between law enforcement and privacy evangelists and how this can be addressed. Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet, but it provides direction for future research.

First off it looks at the different stakeholders involved in payments, including users, merchants, banks and payment providers. It concludes that only three really matter from a privacy perspective: privacy advocates, law enforcement and data holders.

Refreshingly, it does not assume that privacy advocates are inherently dodgy. “We consider a type of privacy enthusiast who is law-abiding and affirms that crimes can be deterred with effective law enforcement, yet believes that errors, breaches, and overreach are a potential future concern.” Of course, law enforcement prefers easy access to payments data for investigations.

While it acknowledges tensions between privacy, law enforcement and technical performance goals, it leans towards the law enforcement end as one might expect of the BIS.

A privacy taxonomy

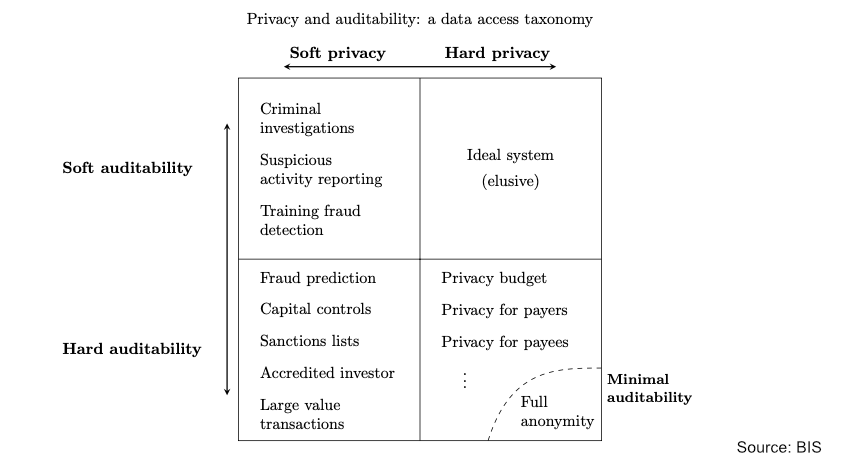

The key contribution of the paper is to analyze solutions across two dimensions: privacy and auditability. Each can either be hard or soft.

Soft privacy is similar to the situation in many jurisdictions today. Payment data is protected, but authorized access to data is possible. Hard privacy includes cases where the user holds a private key to their cryptographically protected records, and not even the data holder has access. It considers cryptocurrency as one example.

Other examples of hard privacy are the privacy enhancing technologies one would expect in a paper of this type. This includes Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) which operate like the 20 question game, except there’s usually a single question, such as is the payee or payer on a sanctions list? The BIS highlights the commonly known weakness of the technology – computational costs and hence scalability. Nonetheless, this is an area receiving significant attention in the blockchain space in the hope of enhancing privacy for transaction. Around three pages of the report explores the pros and cons of various privacy technology options including homomorphic encryption, multi party computation, ring signatures and others.

Moving on to auditability, soft auditability requires law enforcement to have legal permission to get access to data. By contrast with hard auditability, the data is by default inaccessible. Programmable rules can make data accessible based on certain criteria.

Exploring what those criteria might be is another interesting aspect of the report. Examples of hard privacy combined with hard auditability include designs where the payer data is not available. An alternative is when the payee data is not accessible. Other instances include thresholds for payments such as the typical $10,000 mark. Those above the mark are accessible to the authorities. Alternatively, deposits up to a certain budget might be private and not auditable.

Practical trade offs and examples

Cryptocurrency is provided as an example of hard privacy where the desire to “solve crimes” has resulted in the imposition of the travel rule. Some regulators get a copy of all travel rule transactions, which results in “an inefficient dragnet which neither meaningfully prevents crime nor protects the privacy of legitimate users.”

The authors advocate for a “soft core with a hard shell”. This would involve strict data minimization and data retention limits. However, where access to the data is required there should be stronger accountability and transparency. While that sounds sensible, the question is to whom is law enforcement accountable and who bears the cost?

The hard shell aspect would involve using hard privacy for the transfer of data. It suggests that tokenization techniques like that used to shield credit card data from merchants could be an inspiration, but the paper doesn’t flesh this out further.

The final conclusion is that the complexity of the privacy landscape is underappreciated. There’s still significantly more work needed on robust hard privacy technology solutions. And adding traceability for unauthorized access to private data would be a step in the right direction.

As the paper highlights, there’s always a fallback for privacy: Central banks can preserve cash alongside emerging digital payment options.