This morning, the BIS Innovation Hub published a report for the G20 on the lessons learnt from its various central bank digital currency (CBDC) projects across the world. The paper critically assesses the desirability, feasibility, and viability of wholesale and retail CBDCs for domestic use cases, as well as the potential of digital currencies for cross-border use. It highlights some of the challenges central bankers will face as their economies go digital and prepare to roll out a new – potentially disruptive – form of public money.

Prolific BIS CBDC activity

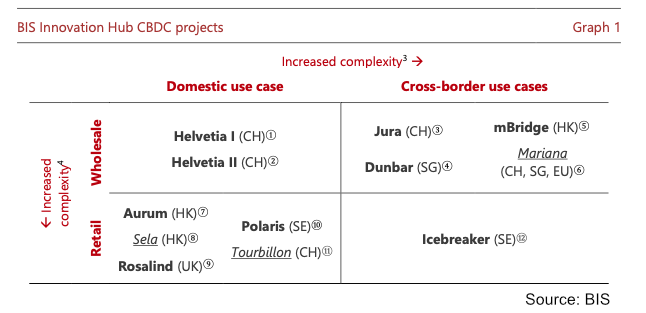

In recent years, the BIS Innovation Hub has partnered with central banks, financial institutions, and the private sector in a dozen projects to help shape research efforts into the development of CBDCs. Most initiatives have focused on either cross-border wholesale (e.g., Jura, Dunbar, and mBridge) or domestic retail challenges (e.g., Rosalind and Polaris). But the BIS has also worked on a domestic wholesale CBDC project in Switzerland (Helvetia), as well as on a cross-border retail one (Icebreaker) with Sweden, Norway, and Israel.

These studies have helped the BIS understand what is desirable (from an individual and societal perspective), feasible (in a technical, legal, and regulatory sense), and viable (mainly in economic terms), carrying forward practical lessons for policymakers as they develop the technical capacity to make a future launch decision.

Domestic CBDC use cases

On the domestic front, project Helvetia demonstrated the functional feasibility and legal robustness of settling tokenized assets with a wholesale CBDC or with a link to Switzerland’s real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system, often called a trigger solution.

However, while the RTGS link is operationally simpler as it would require no significant changes to existing systems, the BIS concludes that the wholesale CBDC approach provides more scope for future innovation and efficiency gains. The Swiss National Bank is evaluating these two models, as well as a private Swiss franc ‘stablecoin’ solution.

As for retail CBDCs, the report highlights their potential to enhance financial inclusion, increase payment efficiency, and maintain monetary sovereignty, but it also notes the challenges related to insufficient uptake. So far, only four jurisdictions (Bahamas, Eastern Caribbean, Jamaica, and Nigeria) have introduced live retail CBDCs, but have all faced difficulties with adoption and fending off concerns around privacy and legal and regulatory implications.

Cross-border CBDCs

Finally, the paper explores the lessons from cross-border use cases for CBDCs in the wholesale and retail space. Reflecting on the experience of projects Dunbar, mBridge, and Icebreaker, it concludes that central banks have several options for making cross-border CBDCs work. A hub and spoke model such as Project Icebreaker connecting separate retail CBDC projects might be easier in the short run. However, a shared common platform is viewed as having more upside.

However, any type of platform will face governance challenges. While there have been private sector collaborations such as Swift, there’s less experience in the central bank sector of multi jurisdictionaly governance. Additionally these platforms will face the same difficulties in managing the multiple legal and regulatory frameworks as traditional cross-border arrangements.