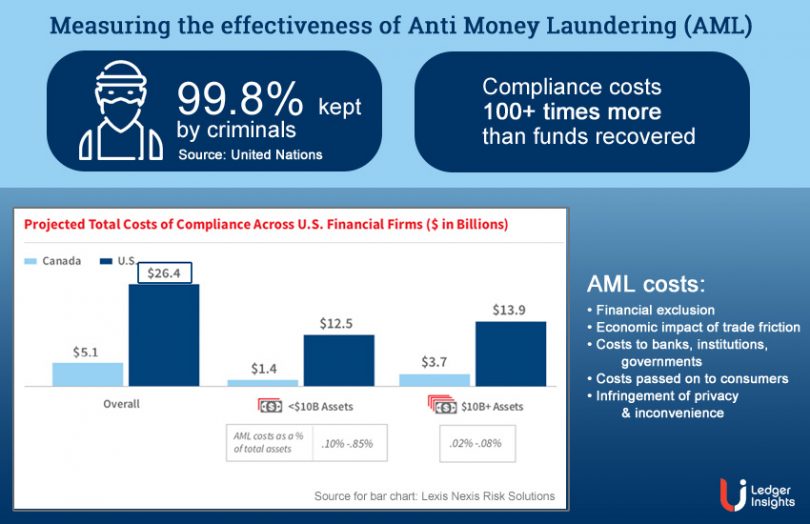

Last weekend, anti money laundering (AML) regulations hit the headlines, following reports that big U.S. banks enable large transactions for the very people that AML rules are meant to stop. Yes, that’s unquestionably bad. But the point that’s missed is not just that AML is failing but the lack of effort to objectively measure whether AML is effective. The fact that a tiny fraction of 1% of criminal proceeds is seized says it’s not working. That’s despite the enormous economic cost borne by SMEs and those financially excluded because of AML. Not to mention the privacy invasion of ordinary people and the Orwellian Big Brother role delegated to banks.

Preventing money laundering is a worthy cause, but if it’s not working, fix it fast or find another away. Don’t allow decades more of economic cost with little gain. Ledger Insights started to explore the topic before last weekend’s news, and we were surprised at the lack of measurement of effectiveness given its negative impact.

Measuring AML’s impact is certainly not easy. But we believe it might be possible.

Article continues …

Want the full story? Pro subscribers get complete articles, exclusive industry analysis, and early access to legislative updates that keep you ahead of the competition. Join the professionals who are choosing deeper insights over surface level news.