This week two sets of data were published showing the growth in blockchain patent registration. Blockchain may prove to be a comparatively tricky area to both register and enforce patents. Enforcement could be harder against public blockchains.

The growth

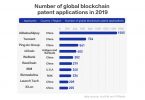

According to Thomson Reuters, the number of cryptocurrency patents filed worldwide went from 521 in 2016 to 602 last year. For blockchain, the figures were 134 and 406 respectively. Last year 56% of Blockchain applications came from China and 22% from the United States.

The Korean patent office also published data with similar figures. They state that the US still leads in cumulative applications, but China has been number one since 2016. Their figures also highlight the rate of growth: 27 cases (2013), 98 cases (2014), 258 cases (2015), 594 cases (2016).

nChain emerged as the second most prolific patent applicant. The company’s Chief Scientist is Dr. Craig Wright, who at one point claimed to be Satoshi Nakamoto, the Bitcoin inventor. In 2017 the company was acquired.

In the press release announcing the deal the extensive patent activity was referenced, and a statement said: “in 2017, nChain intends to make some of its intellectual property assets available to the blockchain community through open source software and royalty-free licensing.”

A company that nChain might view as a competitor, Blockstream, has a broader Patent Pledge that states “Our patent strategy is designed to accomplish one simple goal: ensure that Blockstream technology is available for all to use, royalty-free.”

Why blockchain patents are tricky

There are several reasons why blockchain patents will be harder to register and enforce.

1. Public debate: Many creators now tweet ideas shortly after they’ve had the thought. Twitter, Reddit, Telegram, and Github are forums where people debate the architecture and design concepts. These writings create ‘prior art’ which makes it hard for someone else to claim the idea later. The counter-argument is that this debate will help to mentally stimulate other people who’ll come up variations of the idea. And they might apply for a patent for the adaptation.

2. Whitepapers: While the habit of publishing papers is often ridiculed as vapourware, these too create prior art.

3. Open source: It’s not just the fact that much of the public blockchain software is open sourced, it’s also the process. The code is publicly exposed earlier compared to proprietary software, which again is prior art.

4. Defensive registrations: There are several players like Blockstream. They make it harder for a patent registrant to sue because the defensive patents can be used in chess-like countersuits. Given the community nature of blockchain when patent litigation eventually kicks off, we’re likely to see crowdsourced defence funds. And defensive patent holders may also come to the rescue.

5. Shared nature: Even if someone manages to register a blockchain patent which isn’t invalidated, it’s likely to be awkward to enforce. Patents are easier to enforce if there is a single infringer. In the case of blockchain that will rarely be the case. This point is worth exploring.

Strangers are tough to sue

Blockchains are by definition distributed, and usually, nodes are hosted by several people or companies.

Today in Big Law Business, US patent lawyer Salvatore Tamburo, highlighted a relevant US case Akamai Techs v Limelight Networks (2015). In it, the court found that it “will hold an entity responsible for others’ performance of claim limitations in two sets of circumstances: (1) where that entity directs or controls others’ performance, and (2) where the actors form a joint enterprise.”

Translated from legalese that means if you have a company blockchain, say for your supply chain, then you will be the target of the litigation, even if some of your suppliers host several nodes. That’s the first case.

The numerous consortia that are developing permissioned blockchains seem to fit squarely into the second case of joint enterprise.

The court also defined four requirements for a joint enterprise

-

1. an agreement, express or implied, among the members of the group;

-

2. a common purpose to be carried out by the group;

-

3. a community of pecuniary interest in that purpose, among the members; and

-

4. an equal right to a voice in the direction of the enterprise, which gives an equal right of control.”

When it comes to the public, permissionless blockchains, it will be harder to enforce patents because:

- different functions are often performed by different people resulting in a divided infringement issue. e.g., miners versus validators.

- nodes tend to be anonymous and usually don’t sign normal contracts. This makes it hard to demonstrate a joint enterprise.

- the anonymity makes it problematic to find who to sue in the first place.

The international nature of both public and private blockchains will increase the costs of trying to enforce any patents.

Unfortunately where there’s a lot of money, invariably litigation follows. The Tezos foundation problems are a good example. So it’s only a matter of time before blockchain patent litigation starts. That’s assuming it hasn’t already.

The author is not a lawyer, this article represents simplified versions of legal issues and should not be construed as legal advice.