Bertrand Chen, the Global Shipping Business Network (GSBN) CEO, believes now is the optimal time for the shipping sector to digitize. Backed by three of the world’s biggest shipping container lines and multiple major ports, the blockchain digitization network was incorporated earlier this year in Hong Kong. So far, the non profit technology consortium has launched its first application for cargo release and announced a collaboration with numerous banks to explore trade finance.

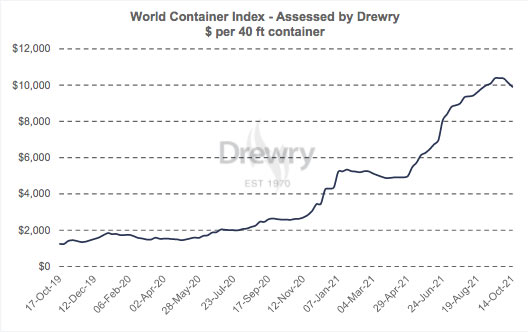

Chen highlighted that the tragedy of COVID-19 has had a silver lining for shipping lines. The stock price of one of its members, COSCO, is more than four times higher compared to the start of 2020. Another member Hapag Lloyd has almost trebled its market cap in the same period. Container shipping costs are higher still, with the world average cost of shipping a container surpassing $10,000 compared to less than $2,000 at the start of 2020.

A normally tight margined business is suddenly flush with money. The companies could buy back stock, invest in environmentally friendly new ships, or explore innovation. Compared to these alternatives, Chen argues that the costs of digitization are comparatively small with a substantial payoff.

“If we cannot digitize now, we’ll never be able to digitize,” said Chen.

And some analysis shows timing to be the single most important factor in startup success.

Controlling your shipping data

GSBN is all about data exchange in the shipping industry. Rather than creating a central repository of the data, the platform allows organizations to keep control over their own data. If they choose to, they can buy and sell data, facilitated by GSBN.

As with many other blockchain networks, GSBN provides APIs so that others can build applications on its platform, not dissimilar to the Apple and Google app stores. Except it has no plans to ask for a 30% cut. That doesn’t mean it’s free, but being non profit will keep charges in check.

In terms of the applications, platform users don’t have to use third party apps. So a shipping line could choose to build its own apps and leverage the GSBN ecosystem to connect with data from terminals and freight forwarders.

We were curious about governance. Who gets to decide the direction of GSBN? In terms of the network itself, GSBN has various committees to inform and help design its roadmap of products.

How does GSBN act as a gatekeeper for adding apps? Chen acknowledged that GSBN doesn’t yet have a written rulebook. The appstore aims to provide options, but it also doesn’t want the network to have spammy apps or have so many apps that people can’t choose.

An eBL is just the first step

Electronic bills of lading (eBL) have been one of the major digitization areas for the shipping industry. Chen is keen for GSBN to support all the major providers such as essDocs, Bolero, Wave, CargoX and others. “Everybody can come and play,” said Chen, welcoming applications that address user pain points. For these app providers, GSBN provides a distribution channel to the GSBN members, which will also include corporates and banks in the future.

As a group of solutions, eBL took a long time to get adopted and is still not there yet. The reason for the delay supports the rationale behind GSBN. “eBL only solves one tenth of the problem, but the other nine are still not digitized and still rely on paper,” said Chen.

“eBL needs to exist within the ecosystem. And what we propose to do with GSBN is (provide) the ecosystem that allows you to offer that. So by itself, it (eBL) is not the killer app. In combination with other apps such as maybe (GSBN’s) cargo release, now your value proposition to the customer is much much stronger.”

The China question

Talking of customers, will some Western clients worry about putting competitor sensitive data on a Hong-Kong based platform where high profile members include Chinese state-owned enterprises? Particularly following actions in the West against Huawei and TikTok.

Chen portrayed these issues as a potential strength for GSBN.

“Blockchain is probably the best technology to address those concerns,” said Chen, because GSBN addresses data sovereignty and data localization. We’ll come back to how in a moment.

With China’s recent crackdown on its technology sector, the country doesn’t want its data to cross borders. “I think this is a general trend where you’ll see more and more countries saying this is very important data, this is critical data, and it cannot leave the country or only under certain conditions,” said Chen.

Hence, there’s a need for platforms such as GSBN that allow data sharing in a compliant way. Chen also emphasized not all the network’s members are Chinese, highlighting major German shipping firm Hapag Lloyd.

Worth the wait

Another European shipper CMA CGM said it would join GSBN when the network was first announced in late 2018 but subsequently dropped out. Given GSBN incorporated this year, it’s been a long time in the making. TradeLens, the initiative from IBM and Maersk, first announced its intentions in August 2018.

One major difference is that TradeLens avoided becoming a joint venture, sidestepping some regulatory compliance and antitrust issues. In contrast, GSBN bit the bullet.

Chen pointed to GSBN not being the only enterprise blockchain to take a while to get going, which is very true. However, he portrayed the delay as an advantage, not least because of COVID-19.

“No one wants to rush into getting married. You don’t want a shotgun wedding,” said Chen, elaborating further, “Where you don’t clearly understand what you’re getting yourself into. You don’t really know your partner.”

So GSBN has benefited from spending time with its partners to understand their desired direction. By taking the time, the idea is clearer and the shareholders are more committed. And that solid foundation is needed because the digitization process is not going to happen overnight. The passage of time has also enabled GSBN to watch the progress of other initiatives.

Using technology to ensure data privacy

GSBN recently announced its hosting arrangements that splits its blockchain infrastructure across two zones, an international one hosted by Oracle and Microsoft Azure and a Chinese one hosted by AntChain and AliCloud.

But what really matters is encryption. If a company wants to share data with the network, it will first be encrypted on the client application, which will usually be deployed within the company’s own data center.

From there, it goes to the GSBN platform, which essentially routes the data to the target recipients and uses the blockchain as a third layer. The enterprise blockchain, Hyperledger Fabric, only stores hashes or fingerprints of the data, which enables the recipient to validate it. For example, a bank can verify that the eBL being shared is the legitimate one because the hash matches.

China has its own encryption standards, but GSBN uses the common international encryption based on U.S. NIST standards. Some have been surprised that China has been more open to international encryption for commercial use in recent years.

A long road ahead

While the stars seem to have aligned for shipping digitization, there’s no question it’s going to be tough. “We’re very lucky. There’s funding. There’s a will to do things differently. In some jurisdictions, the government is supporting people doing things differently,” said Chen. “But even with all this help, it’s going to be hard, because I think some people just don’t like to change.”

GSBN is backed by COSCO SHIPPING lines (COSCO) and ports, Hapag-Lloyd, Hutchison Ports, OOCL, SPG Qingdao Port, PSA International, and the Shanghai International Port Group (SIPG).