While the future is unpredictable, one where digital currencies dominate both money and payments seems a reasonable possibility. The benefits of convenience, lower cost and the possibility of greater financial inclusion seem irresistible. However, An area that hasn’t attracted sufficient attention is the potential increased fragility of money. And this has nothing to do with volatile cryptocurrency valuations. While flaws with various kinds of stablecoin designs have been previously highlighted, the fragility issue goes beyond these and could impact central bank digital currencies (CBDC) as well.

Today, money is reasonably decentralized, with most money creation spread over many commercial banks. Despite the decentralization of blockchain, in a digital currency future, there will be a far smaller number of CBDCs and stablecoins. The issue of being too-big-to-fail will become an even greater one.

A second reason for fragility is that money balances and payment infrastructures are separated in most current systems, making the ecosystem more robust. That makes them more resilient to previously undiscovered cryptographic flaws or software bugs. Tokenized digital currency systems combine the payment message and the money. That critical benefit is also a weakness, a potentially fatal one.

Other sources of fragility have been highlighted elsewhere and are not the focus here. These include the risks of stablecoins that are algorithmic or are backed by high risk assets. And the pressure on treasury and money markets if there’s a run on a gargantuan stablecoin.

The aim is not to dismiss digital currency, quite the contrary, but to see if we can harness its benefits without weakening the foundations of money. This article focuses on two aspects of fragility, with potential solutions in a future piece.

Fewer too-big-to-fail infrastructures

While the graph of European banks below may show a large number of banks, many of us are aware of a far smaller number of really big banks in each country. In a world of stablecoins and CBDCs there’s likely to be one or two big US dollar stablecoins and maybe a CBDC, likewise for the Euro across all eurozone countries.

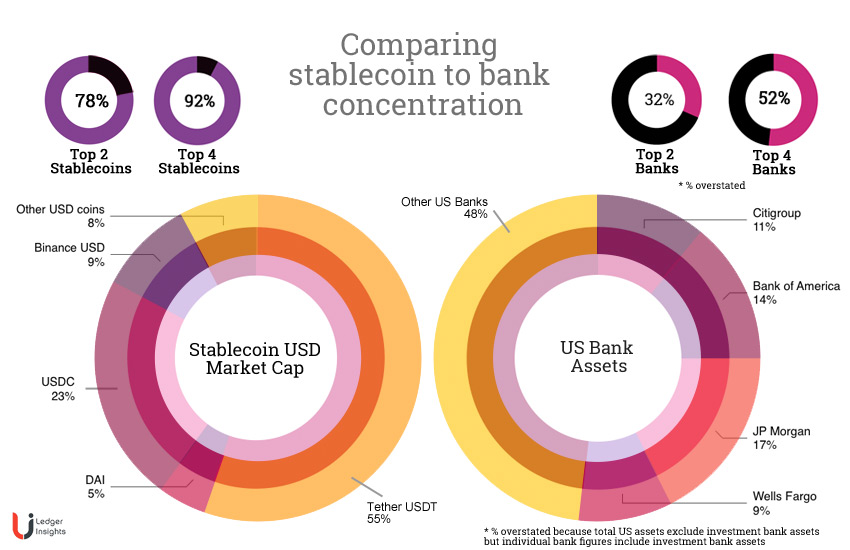

If you assume there are six large banks in each of the 19 countries in the eurozone, that’s 114 large banks, compared to a future with perhaps three big eurozone digital currencies across the entire block, including a CBDC. In the United States, we think of high profile banks such as JP Morgan, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Citi. Between them, these four massive banks hold (*an overstated) 52% of the United States’ $21.1 trillion (March 21) commercial banking assets, with the rest spread over the 5,177 FDIC-insured banks. That’s a lot of concentration. But in a digital currency world, it will be significantly more.

We can already see this concentration in stablecoins, with two dominant dollar coins, Tether and USDC. With assets of $62 billion and $25 billion, respectively they account for 78% of dollar stablecoins.

Imagine a run on one of the big banks in an advanced nation. Now consider what that might look like with a handful of supranational digital currencies.

Also, consider one manner in which the potential for runs is currently addressed: by reducing access to high value payment systems. But in a world of tokenized digital currencies, the money and the payment system are one.

Current infrastructures separate payments from money balances

If you look at most payment systems today, whether it’s SWIFT for cross border payments or domestic payment systems, they are all messaging platforms. The money itself sits either at commercial banks or commercial bank balances at central banks.

Hacks related to SWIFT have happened, although they’ve generally compromised a particular bank’s SWIFT credentials. A notorious recent example is the 2016 $81 million Bangladesh Bank heist.

As with the Bangladesh example, if there is a cyberattack on a payment system, it could impact a few large payments that have gone awry. Payments using that system could temporarily be halted before resuming.

But the bigger risk is a software bug or cryptographic flaw uncovered in widely used software, as happened several times in the last decade, with one example being the 2014 discovery of the HeartBleed bug.

In a world of digital currencies, the payment system and the currency are one and the same. So a successful cyberattack or coding flaw may potentially impact large amounts of currency holdings or more likely undermine confidence in that currency, triggering a run. And not just any run, a run on a scale not previously seen.

While many central bank papers emphasize the importance of cybersecurity, this is far more than a tickbox to-do list item.

One politician that has publicly acknowledged the risks is Singapore Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam, who chairs the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). Talking about cyber issues earlier this year, he said it is “one of the reasons why I myself favor this biodiversity. And favor not having one big dominant central bank digital currency solution even within our own countries, let alone internationally.”

“You don’t want the whole system blowing up at once,” he said.

* If investment banking figures were excluded the true percentage would be smaller. The total assets of the big four banks (including investment banking assets) were compared to total commercial banking figures from the Federal Reserve.